Genealogical researchers hope to document their family as far back as they can, leaving a legacy for their descendants to enjoy. There is the hope that we might uncover skeletons in the closet or solve a family mystery. A bonus would be to make a link to someone famous.

I was recently researching the Case family (Dad’s maternal side of the tree – Henry Moore Case (abt. 1817-1888) was my third great-grandfather, the father of Frank Herbert Case, grandfather of Harry Maulden Case and great-grandfather of Kathleen May “Kay” Case, Dad’s mother). Henry had long been a challenge for me. I had a clue as to his father’s name – George – as he was living with him in 1851 when the census was taken, and I knew from that where he was born, London, England. However, I did not know if the woman living with them in 1851 (Elizabeth) was his mother, or his father’s second wife, or if he had any siblings.

Henry Moore Case was a tailor by trade, serving an apprenticeship in Sheffield, Yorkshire, under a Joseph Harris, with whom he was living along with two other junior tailors in 1841. It was common under the apprenticeship system for masters to offer room and board along with training. In 1851, at the time of the census, he was a qualified tailor and living back with his father in St Pancras, London. By 1857, however, he had moved to Maidstone in Kent, where, in 1860, he married Caroline Cook. They went on to have twelve children and by the age of 65 he was still in Maidstone, a master tailor who employed three men.

My research indicates Henry had two brothers: an elder brother, George William Henry Case, born in 1815, and William Tierney Case, born about 1820. Both Henry and George Jr had George and Sarah Case as parents, their father George was listed as a Lace and Fringe Maker at their baptisms, and both were baptised at St Martin-in-the-Fields with their parents’ residence given as 19 Oxford Street. It isn’t too much of a stretch to see how Henry became a tailor when his father was a lace and fringe-maker.

Henry’s mother Sarah must have died about 1817, possibly as a result of childbirth, as there is a record of George remarrying that same year to Elizabeth Williams (maiden name unknown), herself a widow. William Tierney Case was baptised in 1820, just as his half-brothers were, at St Martin-in-the-Fields. His father is listed as George, still working as a Lace and Fringe Maker and living in Oxford Street. Confusingly, his mother was listed as Sarah. This must have been either a mistake from the curate – or perhaps was Elizabeth’s full name was Elizabeth Sarah. Another child, Henry again (no middle name recorded) was born in 1821, but died a few days after birth. His baptism had his parents correctly recorded as George and Elizabeth – but, unlike his brothers, he was baptised in Ledsham, Yorkshire. The baptism noted they resided at 19 Oxford Street, London, confirming that they were definitely the same family. Possibly Elizabeth was from Yorkshire, or there were Case relatives there, or George had gone there for work briefly.

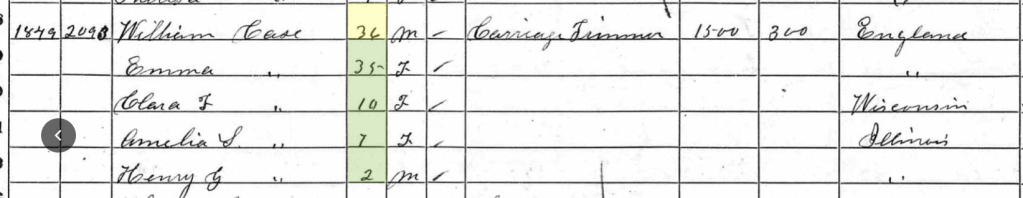

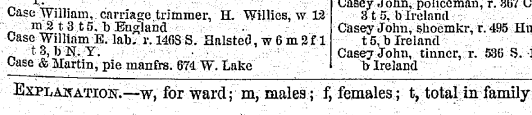

William Tierney Case became a coach trimmer, an allied trade to his brother Henry (the tailor) and directly related to his father’s trade of lace and fringe-making. Coach trimmers worked for coach or carriage builders and generally began work once the carriage was painted or varnished. They were skilled craftsmen, wielding awl, needles, glue, pins and tacks and employed patterns, knives, scissors to cut all types of cloth and leather, selecting from stocks of cord, rolls of coach lace and thread. They needed general carpentry skills and did upholstering as well as curtains, ceiling, door and floor coverings. William married Emma Neale in 1849 at St Paul’s Covent Garden. A month later, he and Emma emigrated to the United States, landing at New York. They briefly lived in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, before making Chicago, Illinois their permanent home.

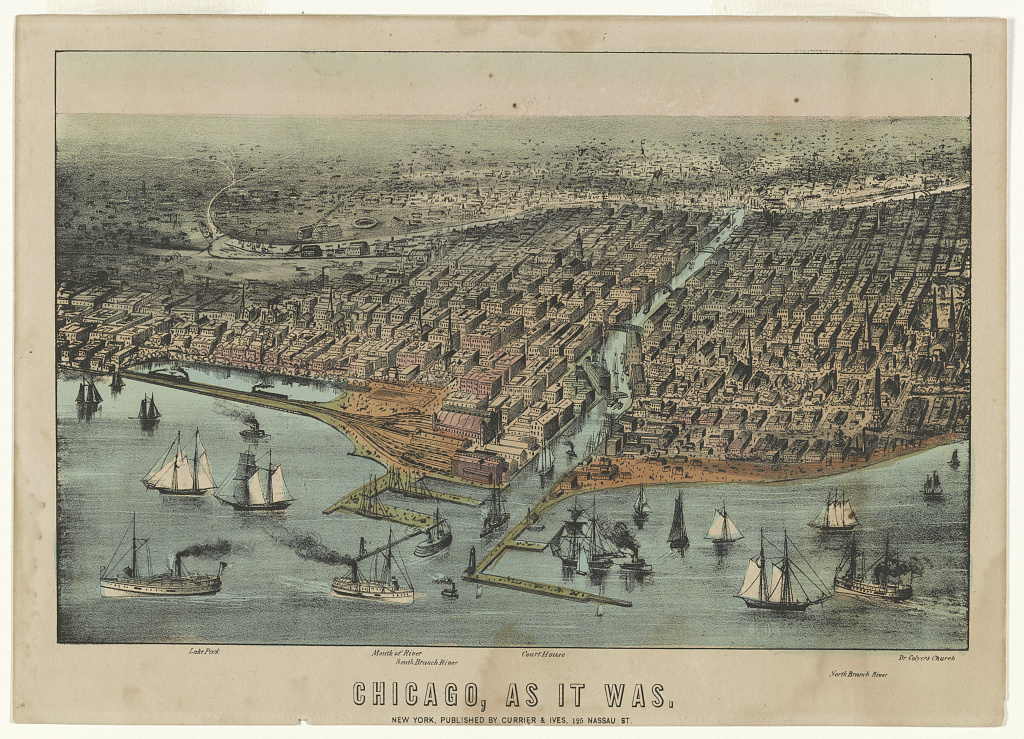

The 1850s was a time of expansion in America. Immigration increased due to the Irish potato famine, civil unrest throughout Europe, and a desire for more land to farm. The ongoing industrial revolution saw the first elevator being installed, the first sewing machine for home use going on the market and the invention of an inexpensive method of producing steel.

During this time, America was also experiencing increasing tension and disputes over slavery. In 1860, Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln, running on an anti-slavery platform, defeated three opponents in the campaign for the presidency. Although Lincoln won the Electoral College by a large majority, the popular vote revealed how split the nation was. His election led to the secession of the southern states and resulted in the American Civil War (1861-1865).

William was listed in the Chicago City directory for 1852 as a Coach Trimmer for Welch & Co (Benjamin C Welch’s carriage factory was on Randolph street, corner of Ann), living near the corner of Lake and Halsted. He and Emma had four children, three of whom made it to adulthood. They lived for over 20 years at 15 S Ann St (now Racine Ave).

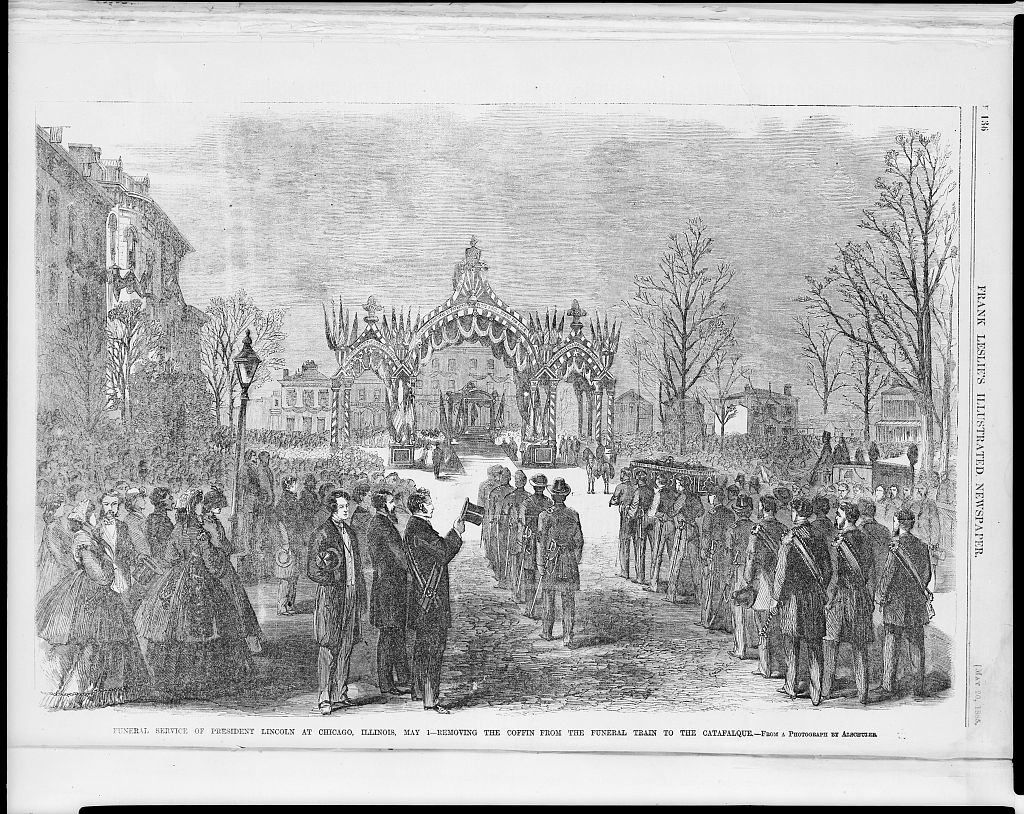

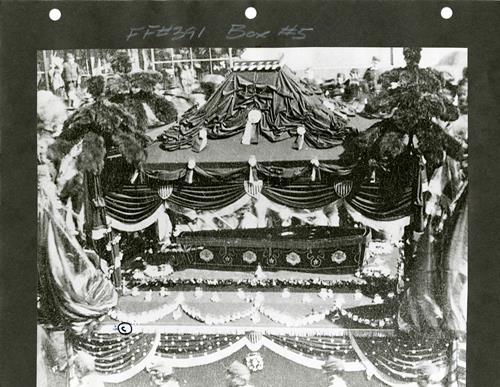

In April 1865, five days after the Confederates surrendered, Abraham Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth. Here is our (slightly tenuous) link to fame. William Tierney Case was asked to trim the catafalque in which President Lincoln’s body was paraded through the streets of Chicago.

Retrieved from the Library of Congress

Slowly at Twelfth Street and Michigan Avenue the funeral train came to a stop. Under a huge reception arch of side arches, columns, and Gothic windows in the lake shore park near by, the eight sergeants carried the coffin and laid it on a dais. The pallbearers and guard of honor made their formation around it. Throughout brasses and drums gave a march written for the occasion, ‘The Lincoln Requiem.’

Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, Volume IV, p. 411, in The Funeral Train of Abraham Lincoln, blogpost Abraham Lincoln’s Classroom

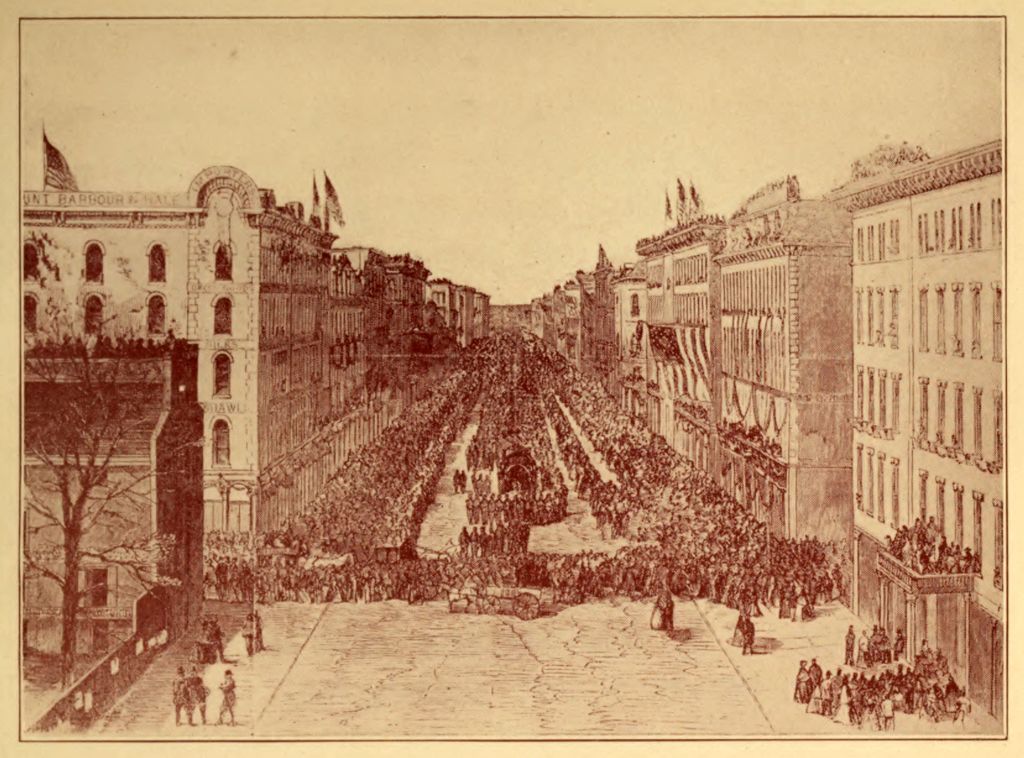

…The coffin was then placed in the funeral car or hearse, prepared expressly for the occasion, and the funeral cortege passed out of the Park Place into Michigan avenue, and fell into procession… It was a wilderness of banners and flags, with their mottoes and inscriptions. The estimated number of persons in line was thirty-seven thousand, and there were three times as many more who witnessed the procession by crowding into the streets bordering on the line of march, making about one hundred and fifty thousand who were on the streets of Chicago that day, to add their tribute of respect to the memory of Abraham Lincoln.

J. C. Power, Abraham Lincoln: His Great Funeral Cortege, from Washington City to Springfield, Illinois with a History and Description of the National Lincoln Monument, p. 95 and 99.

Lincoln’s body lay in state until 8pm at City Hall, Chicago. Civil War artist correspondent, William Waud described it as such: “The ceiling is draped black & white. The walls draped in folds all black with flag trophies at certain distances. The Catafalque is covered with black cloth & velvet all black with silver fringe & stars. Inside of d[itt]o & the pillars white with the exception of the ceiling inside the canopy which is black with white stars cut out through which the light is admitted to fall on the coffin.”

The coffin was opened for public viewing at 6pm and lasted through the night and all the next day. After the courthouse doors closed at 8pm, a torchlight procession escorted Lincoln’s casket back to the train, now destined for its final stop, Lincoln’s hometown of Spingfield, Illinois.

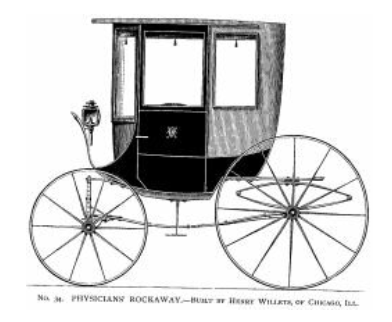

William continued carriage trimming through the 1870s, for a time employed by Henry Willets.

Built by Henry Willets, Chicago, Illinois. Painting.–Body, black; running-gear, black, striped with one fine line of gold bronze. Mountings, silver.

William lived through a time of tremendous change for carriage craftsmen. He had been born when carriages were everywhere and used for many purposes. Delivery wagons contained fresh groceries, newly-cut lumber, supplies of every description. Elegant private coaches moved gracefully down avenues, carrying rich residents to the office, the opera or a fancy meal. Heavy steam pumpers put out countless raging fires in city tenements. By the end of the nineteenth century, industrialisation had caught up, large mechanized factories had all but replaced small carriage shops and the ‘horseless carriage’ began to be experimented with.

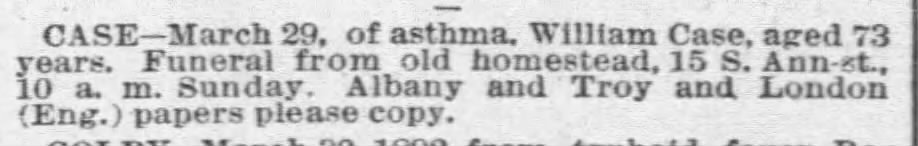

William died in 1892. His death was recorded with a few simple lines in the Chicago Tribune.

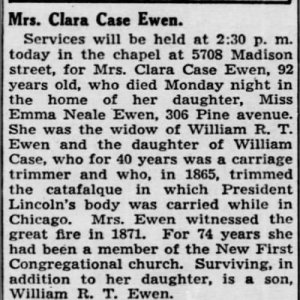

When William’s daughter Clara (Case) Ewen died in 1942 in Chicago, her obituary finally made mention of her father and his unique claim to fame.

Clara Case Ewen, obituary, Chicago Tribune (Chicago, Illinois) 15 Jul 1942, p.16

William is buried at Forest Home Cemetery, Forest Park, Cook, Illinois, USA along with his wife Emma, daughter Clara and son, Henry George Case.

Sources:

America in the 1860s, Humanities Texas, Sep 2014; online article <https://www.humanitiestexas.org/news/articles/america-1860s : accessed 27 Sep 2023>

Americasbesthistory.com Timeline – The 1860s, America’s Best History <https://americasbesthistory.com/abhtimeline1860.html : accessed 27 Sep 2023>

Kinney, Thomas A. The Carriage Trade: Making Horse-Drawn Vehicles in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004.

Find A Grave, database (http://www.findagrave.com : accessed 27 Sep 2023), entry for William Tierney Case (1819-1892), Memorial No. 123152316, Records of the Forest Home Cemetery, Forest Park, Cook, Illinois; page created by Dave H 12 Jan 2014 , maintained by klast.

Lehrman Institute. Abraham Lincoln’s Classroom. Blog <https://www.abrahamlincolnsclassroom.org/>

The Newberry. ChicagoAncestors.org. Website <https://chicagoancestors.org/>

Subscription databases: Ancestry, FindmyPast, newspapers.com, Fold3

Have you found any connections to fame or famous people in your family? Are you a descendant of any of the Case family? Please get in touch. I'd love to hear your stories! -- Nicola

Leave a comment