As a sixteen-year-old I received the book For the Term of His Natural Life (1874) from my paternal grandmother, who always encouraged my love of reading. It is about an aristocrat who, falsely accused, is transported to Van Diemen’s Land, suffering extreme cruelty and violence at the hands of his jailers and fellow convicts. It greatly affected me. Little did I know at the time we had our own convict amongst our relatives!

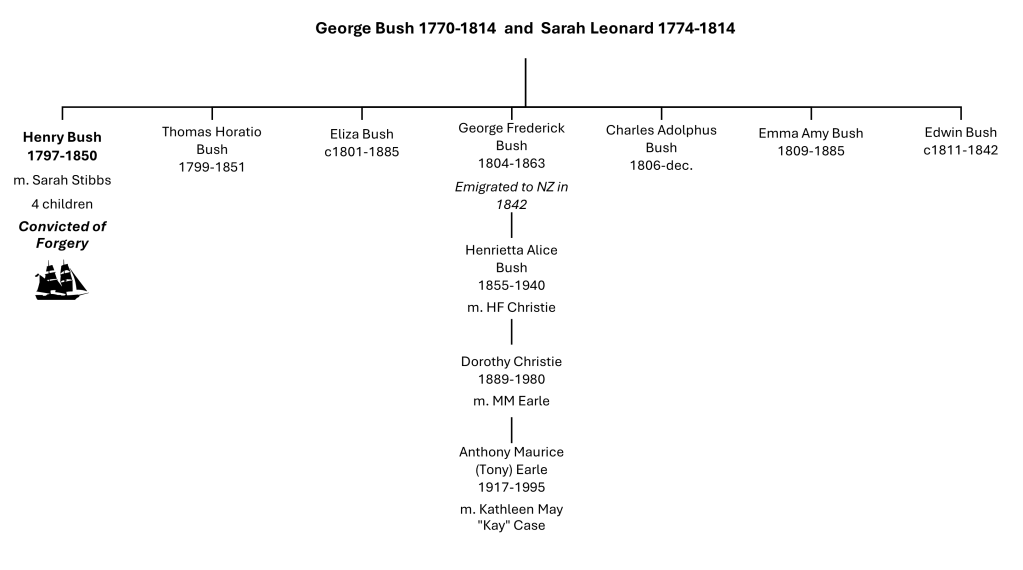

Henry Bush was brother to my third great-grandfather, George Frederick Bush 1804-1863. He was one of seven children born to George Bush 1770-1814 and Sarah Leonard 1774-1814, of Wick and Abson, Gloucestershire, England.

Early Life

Henry was born into a relatively wealthy family. Baptised on 19 June 1797 at Abson, Gloucestershire, his father, George, was a cornfactor (trader in grains and corn) and later became a successful maltster and brewer.

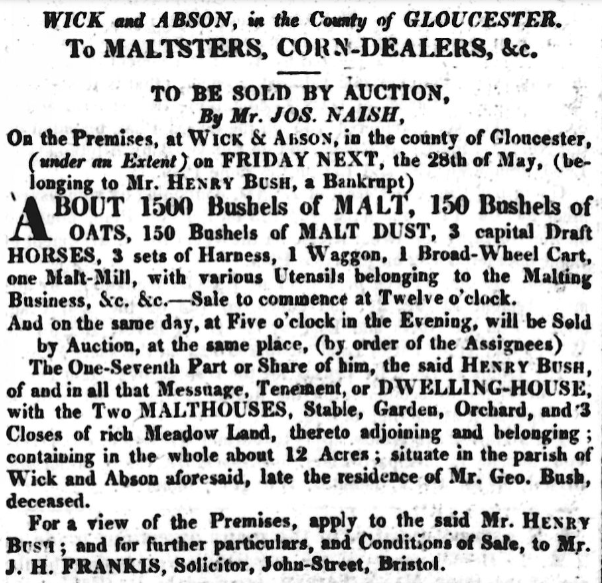

Henry briefly followed his father into the trade. Perhaps he did not possess a good business head, perhaps he was a schemer or just eternally optimistic, but fortune did not favour him. After his father’s suicide in 1814 (after his mother Sarah died in childbed) Henry placed an advertisement to let the family home, described as consisting of an “entrance hall, 3 parlours, drawing room, 5 bedrooms with garrets.”1 In 1819 it was listed for sale. Interested parties were advised it now belonged “to Mr. Henry Bush, a Bankrupt.”

In the Spring 1819, Henry married Martha Stibbs, of Stout’s Hill, his half-first cousin, at St Mary’s Church, Bitton, Gloucestershire.2 Now bankrupt, Henry was forced to sell his one-seventh share in his father’s estate.3

Henry and Martha’s family grew between 1824 and 1835. A ‘general dealer’, Henry made some sort of financial arrangement with his brother-in-law, John Stout Stibbs. In 1826, John requested accounts for him be sent to “Mr Henry Bush’s, Maltster, Wick” in order they be paid.4 Possibly this was the first indication of trouble brewing between the Stibbs and Bush family.

After Henry and Martha had their fourth child in 1835, the marriage became strained and Henry left the family home.5

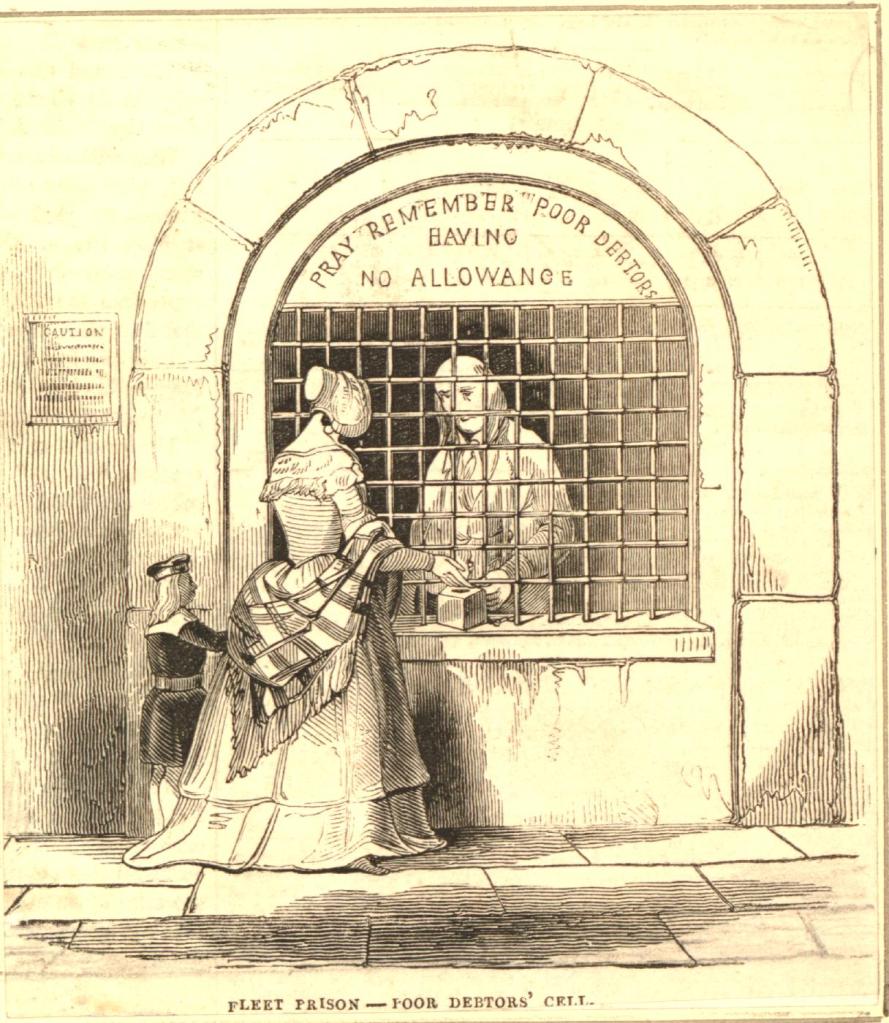

An application for Henry to be discharged as an insolvent was heard at the Courthouse, Portugal Street, Lincoln’s Inn Fields in April 1834.6 The judges were not satisfied and he was sent to Fleet Prison. On 14 October 1836, he was discharged. Prison records note among his creditors one John Stout Stibbs, his brother-in-law.7

In March of 1838, Henry appeared before the courts again, this time at the Court for Relief of Insolvent Debtors in Gloucester, described as “Henry Bush, first of the Fleet Prison, in the City of London, and late of Stouts…Hill, Wilsbridge, near Bristol…of no trade or business.”8 He was ordered to be discharged.9

Henry’s wife Martha appears in the 1841 census living independently in Longwell Green village with three of their children; one being at school in Bristol.10 It is likely, given the timeline set out in the trial, Henry was at that time in Southwark, the Fleet or the Kings/Queen’s Bench Prison – all debtor’s prisons.

Debtors prisons had privileges unlike regular prisons, including being allowed visitors, their own food and clothing, and the right to work at a trade or profession as far as was feasible. Fleet Prison even had a begging window, where the poorest prisoners could ask for alms. Prisoners could not leave (unless they bribed their warders) until they had either paid or been released by their creditors.11

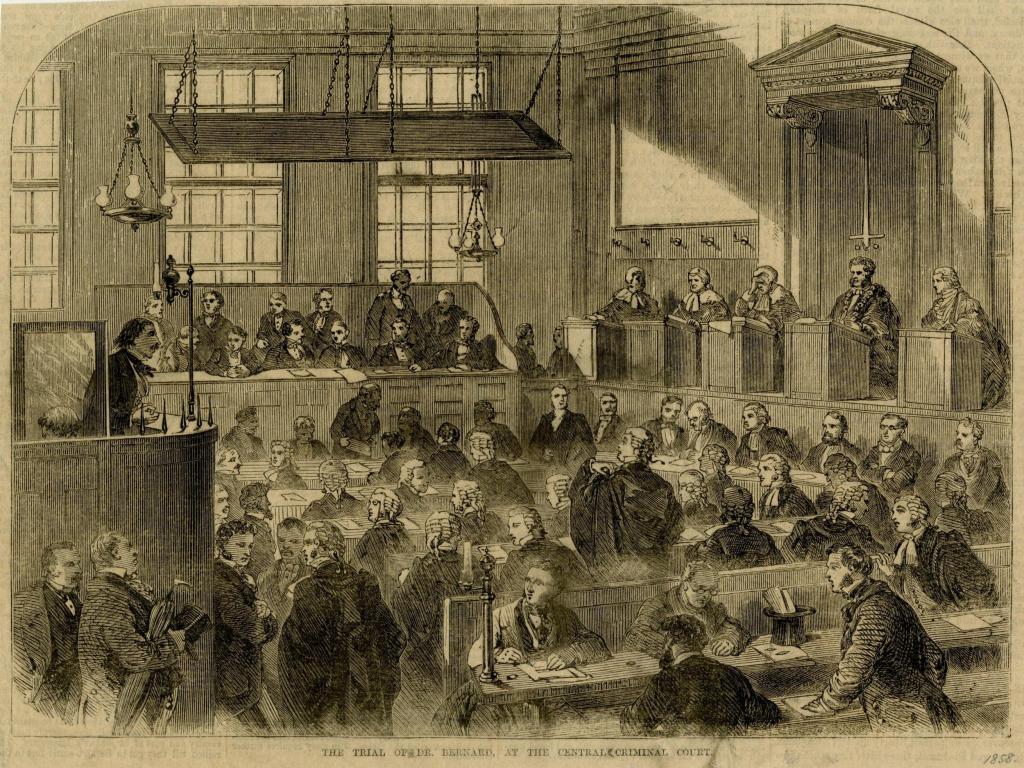

The Trial

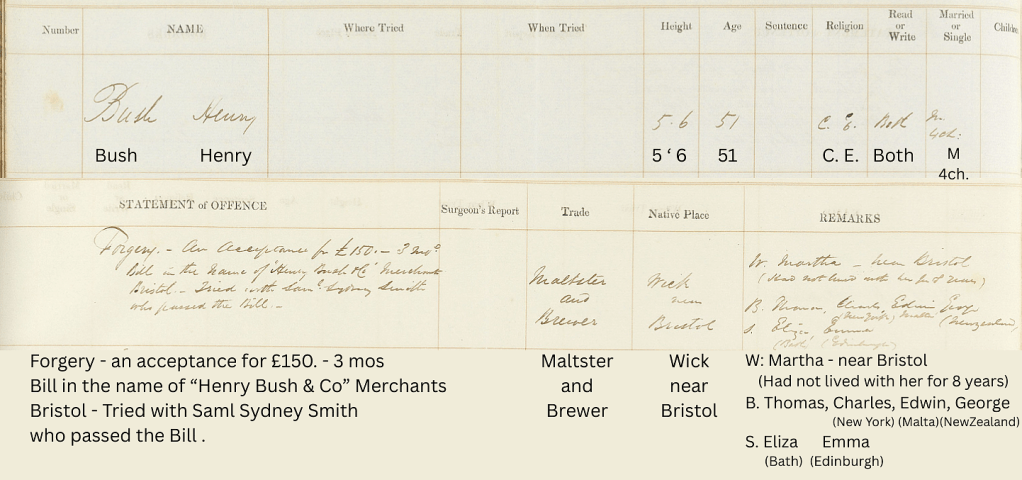

Henry first appeared as a witness for a prisoner, Samuel Sydney Smith, on trial for “forging and uttering a bill of exchange.” He appeared before the jury in August 1843, but quickly came under suspicion of collusion with Smith, a previously convicted felon. The bill of exchange, in the name of Henry Bush & Co., attempted to defraud Samuel Lyon, a silversmith and jeweller, of £150.12

In Bristol at the time existed another firm of Henry Bush & Co., in Baldwin Street. That company was well-respected and successful, and its namesake a member of the town council. No doubt Henry and Samuel were aware of this and hoped when Smith presented the bill to Lyons, the name Henry Bush & Co would immediately evoke a sense of trust.

“£150. Bristol, 17th February, 1843.

“Three months after date pay to the order of Mr. Smith the sum of one hundred and fifty pounds, for value received, as advised by the Bristol Old Bank. “HENRY BUSH and Comp.

“At Messrs. Prescott, Grote, and Co., Bankers, London.”

Endorsed, “S. S. Smith.”

In the dock, Henry did himself no favours. Initially, he stated he lived at Southall [some papers reported Stoke’s Hill, some Stout’s Hill], near Bristol, farming “about fifty acres of arable land”, paying £120 a year.” In the past, he had been “in the corn trade…in the name of Henry Bush…in February last I was carrying on business in the name of Henry Bush and Co.” He admitted, however, “…this bill is my handwriting.”

Under intense questioning, Henry’s lies were gradually exposed. At first, he only stated he had ‘seen’ Smith in London, but finally elaborated – they had met at the King’s Bench debtor’s prison.

Farming in Southall was forgotten; details regarding his business vague. “I [lived at]…42 New Compton-street, on the 23rd of Feb.—my landlord’s name was Bailey—I always sleep there—I pay 3s. 6d. a week—6d. a night.” Henry was a “general dealer” but had “no warehouse…no shop or counting-house. I do not keep an account at any banker’s…I cannot recollect what business I did in Feb. or March, April, May, or June.”

The prosecutor assassinated Henry’s character, forcing him to admit “I have been discharged under the Insolvent Act, and…a bankrupt…I was in gaol for two years…I have been in prison for defrauding the Excise…for two months.”

In September 1843, Henry Bush and S. Sydney Smith were convicted at the Central Criminal Court, formerly the Old Bailey, of forgery. They were given life and sentenced to transportation.13

Transportation

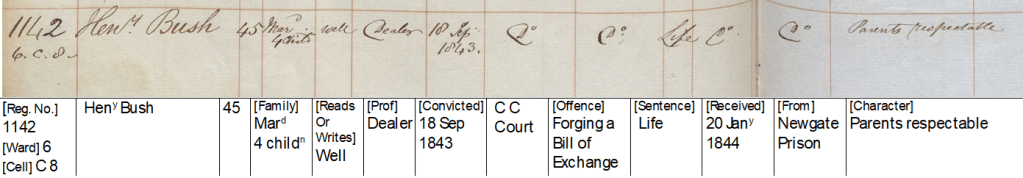

Initially returned to Newgate Prison, Henry was transferred to Millbank Prison on 20 January 1844 where he awaited transportation on the ship Blundell.

On 9 March, the prisoners were conveyed down the river in steam-boats belonging to the Waterman’s Company, under guard of a detachment of the 58th Regiment. The Blundell lay off the Royal Arsenal, at Woolwich. She carried 324 passengers, of which 210 were convicts, her destination being the penal settlement of Norfolk Island.14 The voyage took 102 days.

TheBlundell prison ship was the first to adopt a “new system”, whereby each prisoner occupied a berth of 20 inches (about 51 centimetres!) and was “sufficiently long” to enable movement without disturbing other prisoners. It was hailed a success. Forty-one were recorded sick by the surgeon but there no deaths – one Sergeant of the Guard did manage to shoot himself in the finger, requiring amputation, but it healed nicely.15

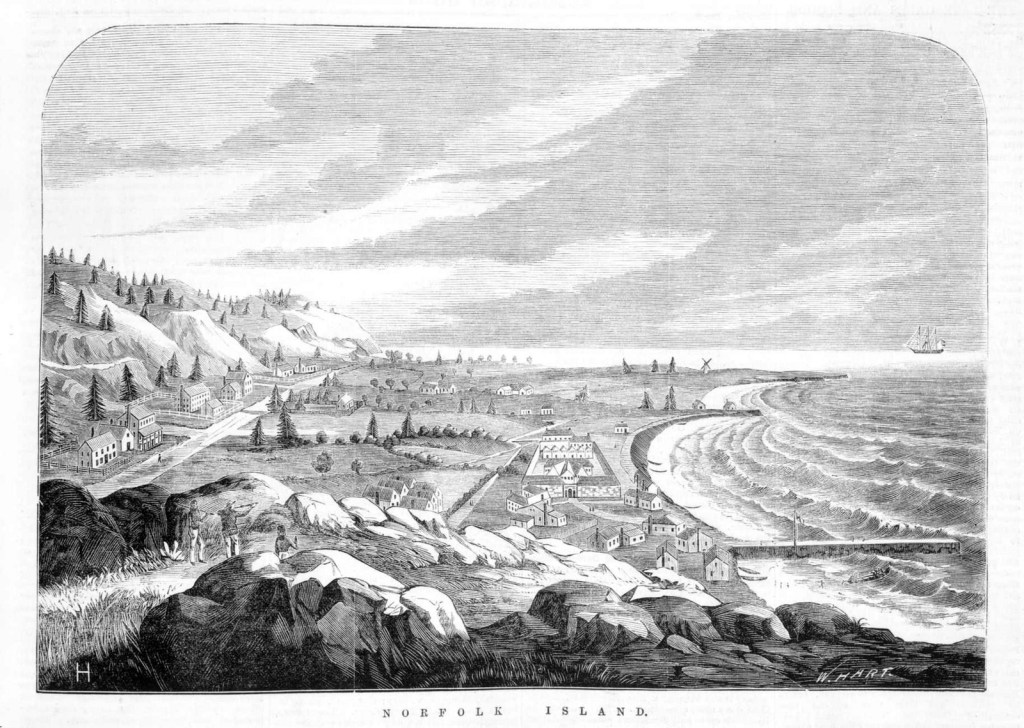

Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island is situated about 1500km northeast of Sydney in the South Pacific Ocean. It is approximately 8km long and 5km wide. When Henry arrived on the island, it was administered by the Governors of New South Wales; by the time he left, administration had been transferred to Tasmania.

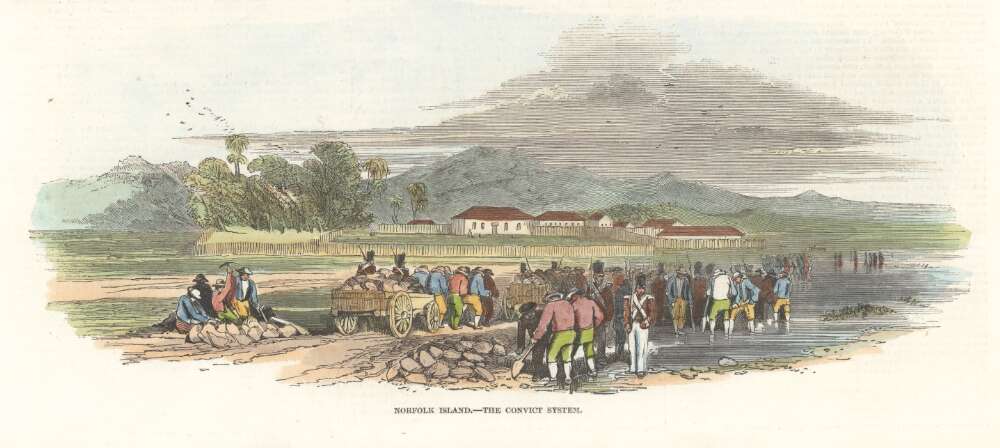

Henry was sentenced at a time when the government adopted the method of transportation known as the ‘Probation’ system. Convicts were expected to progressively improve by progressing through a five-stage system: (1) detention at Norfolk Island or on the Tasman Peninsula for 2-4 years (only the worst criminals, those sentenced to ‘life’ or fifteen years); (2) removal to work government gangs in various parts of the colony, still incarcerated; (3) grant of a leave pass to work under certain conditions; (4) gain of ticket-of-leave; (5) absolute pardon.16

Punishments on Norfolk Island were brutal and excessive and life was harsh. Those sent to Norfolk Island could expect days spent labouring in the fields or constructing great stone buildings. Breaking rules, or displeasing guards, might see you bound by heavy chains, or irons. Other punishments included reduced rations, solitary confinement or the crank mill. Murders, suicide pacts, mutinies, rape and informer networks were everyday features of prison life. Inmates were disciplined for singing, smiling, ‘not walking fast enough’ and possessing tobacco.17

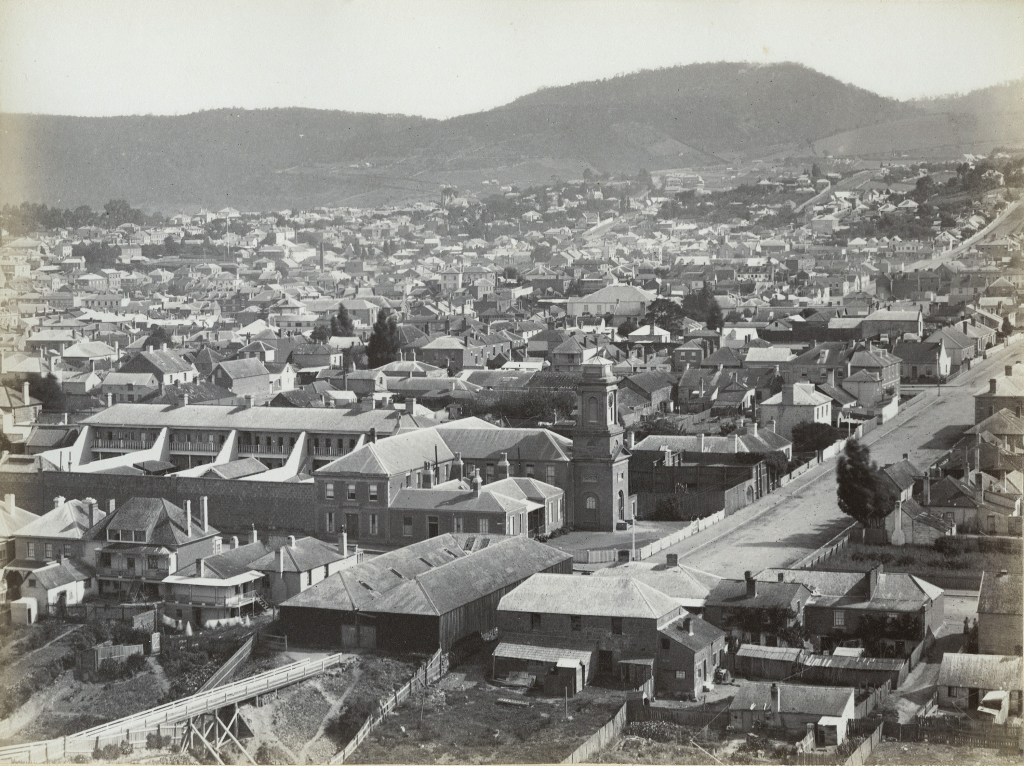

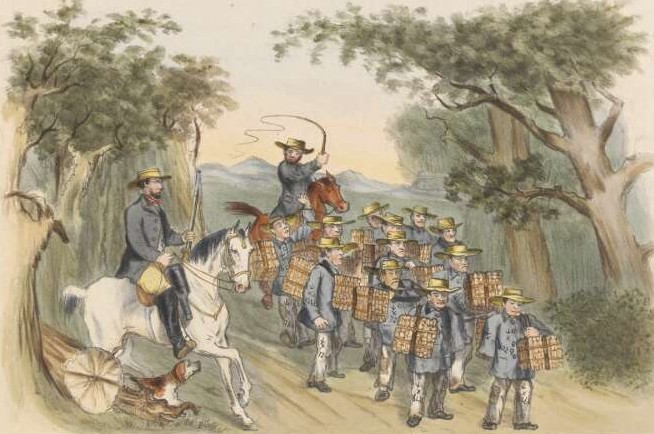

National Library of Australia ID 235145.

Henry served two and a half years hard labour in a work gang before serving under Norfolk Island storekeeper Samuel Padbury in 1846 as a “storeman and writer” for the Convict Stores.18 The Commissariat consisted of three floors and a basement. Being able to read and write, Henry could be put to good use doing administrative tasks other convicts could not.19

Notes from Henry’s convict record from this time record the offence of “having money in his possession”, causing his detention time to be extended by two months.20

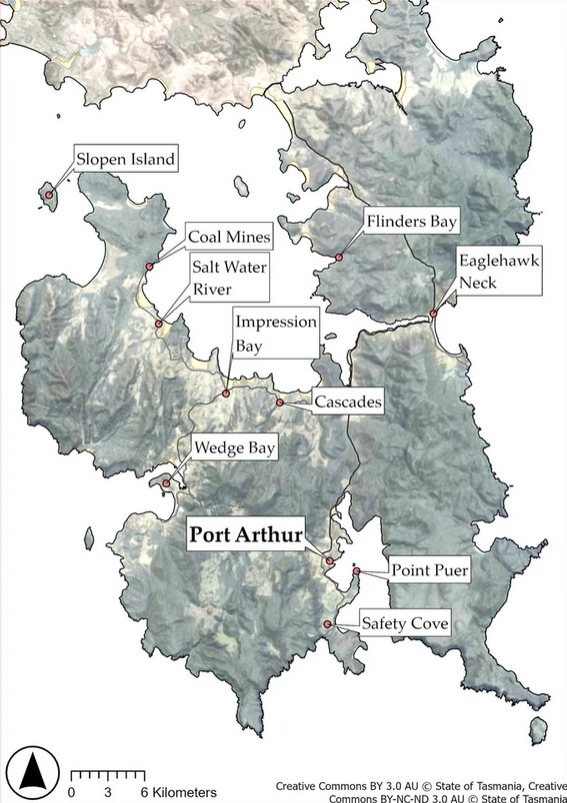

Tasman Peninsula

In April 1847, Henry was transferred on the prison ship Pestonjee Bomanjee to the Impression Bay probation station at Premaydena on the Tasman Peninsula. There he served as a messenger on the signal staff at Halfway Bluff.21

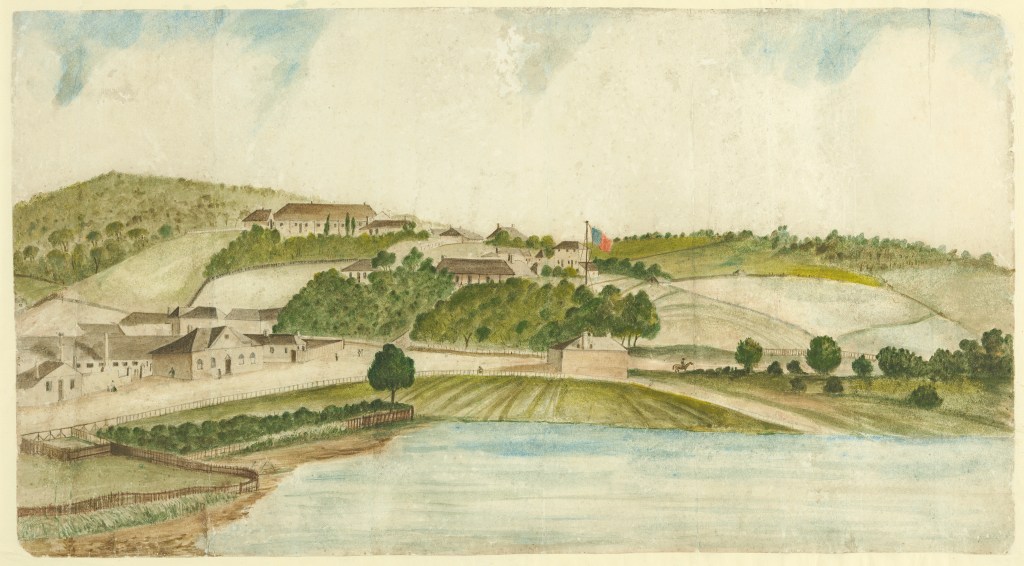

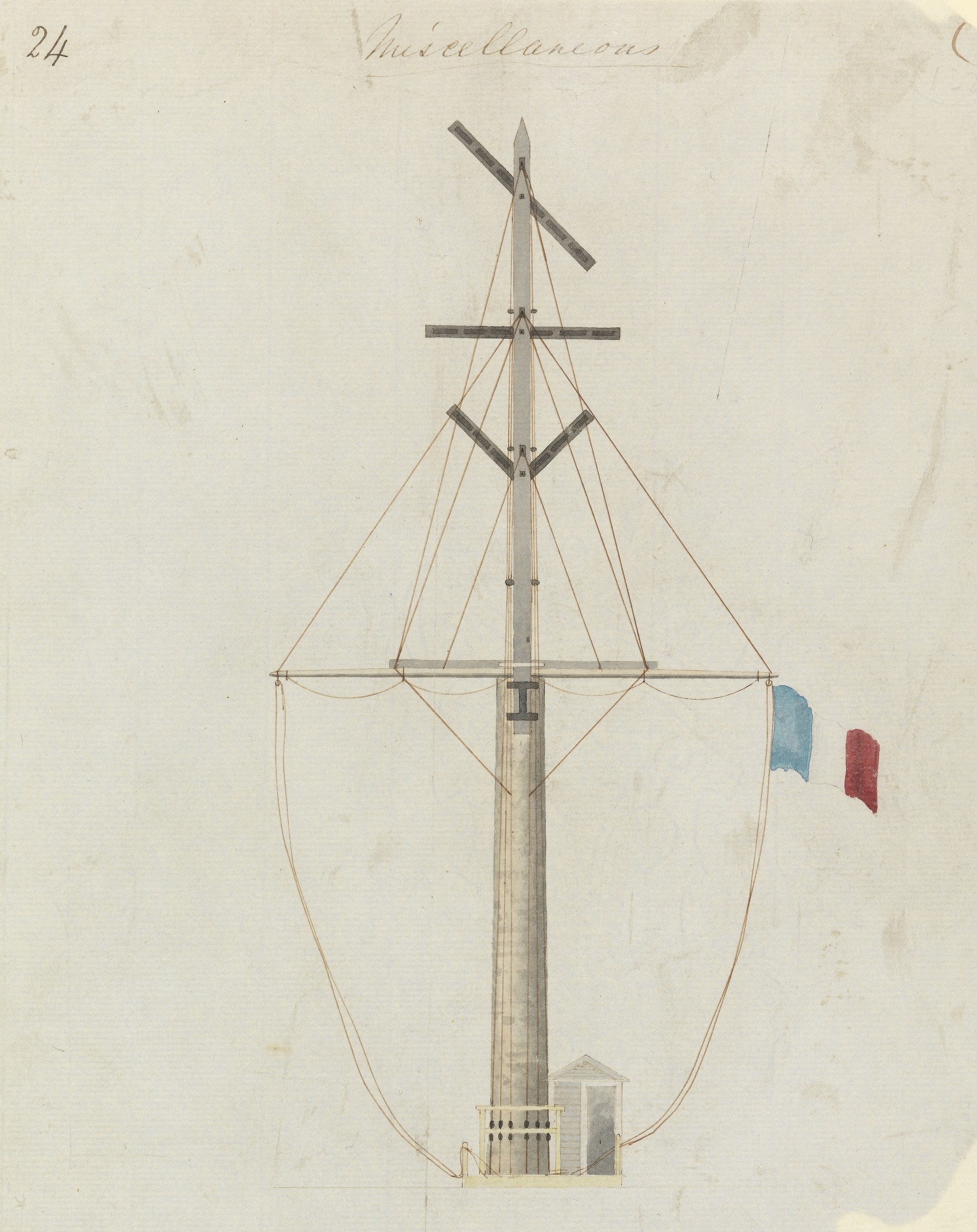

Between 1830 and 1877 the whole of the Tasman peninsula operated as a restricted penal environment. The penal hub was at Port Arthur, Premaydena was part of a series of outstations. A network of signal stations used flags or moveable arms mounted on tall masts or posts to communicate with incoming ships and relay messages about escaped convicts and other happenings across the settlement. Experienced operators could send a message from Port Arthur to Hobart Town in under 15 minutes.

“The semaphores were primarily staffed by good-conduct prisoners nominated as constables. Quartered in small huts at each semaphore and equipped with a telescope, a clock, and a code book, the signalers were expected to remain vigilant. In the event of a night time alert, signal fires were used.”22

Henry must have enjoyed the greater degree of freedom afforded him in his ten months here.

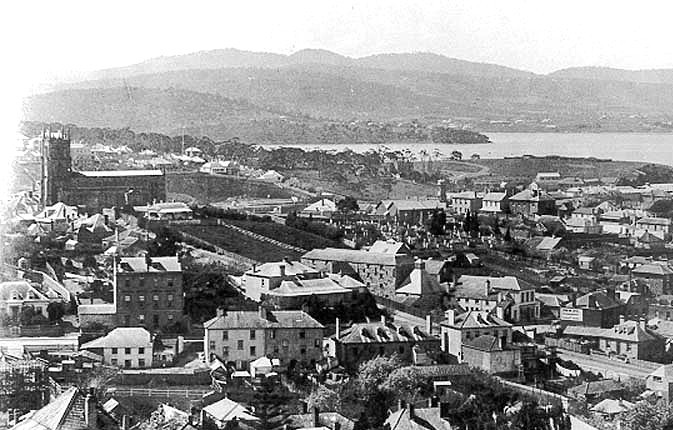

Hobart Penitentiary

With five years served of his sentence, Henry moved to the third stage of the probation system and was able to work under specific conditions. Transferred to Hobart Penitentiary in Campbell Street, Hobart Town, Henry became a PPH (Probationary Pass Holder 3nd Class) in March 1848.23 Most pass holders worked for private employers and received a wage. Although it was not a market wage (these were coerced workers) it was a notable incentive, and more preferable to gang labour.24

Henry’s conduct record includes the best description we have of him:

- 5’6″

- fresh complexion

- medium head

- light brown hair, bald

- no whiskers

- narrow visage

- high forehead

- fair eyebrows

- grey eyes

- medium nose

- large mouth

- medium chin

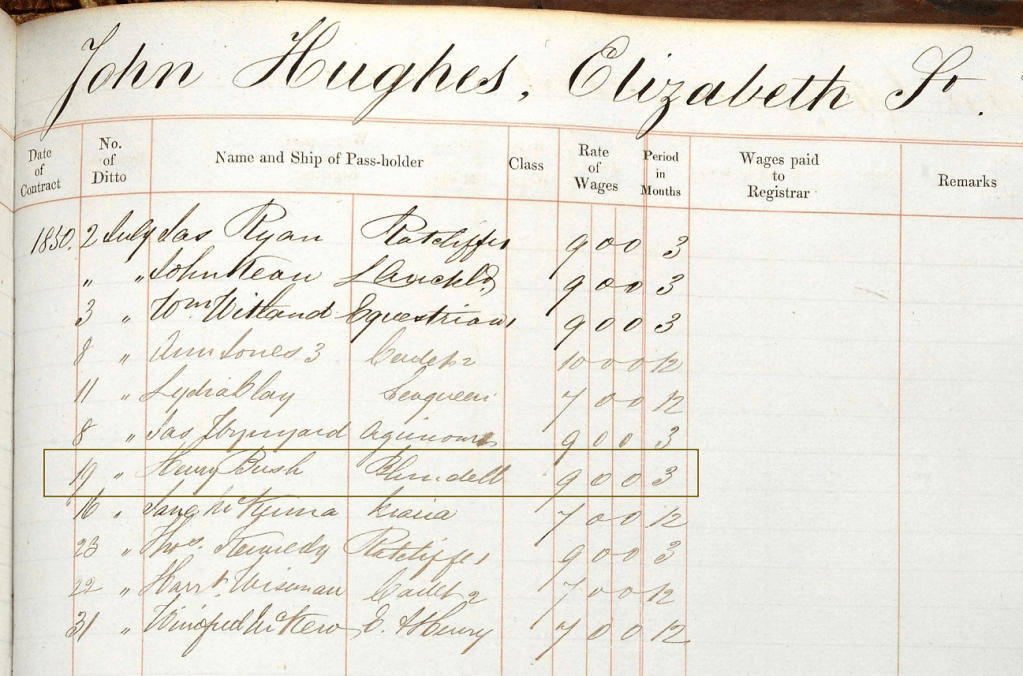

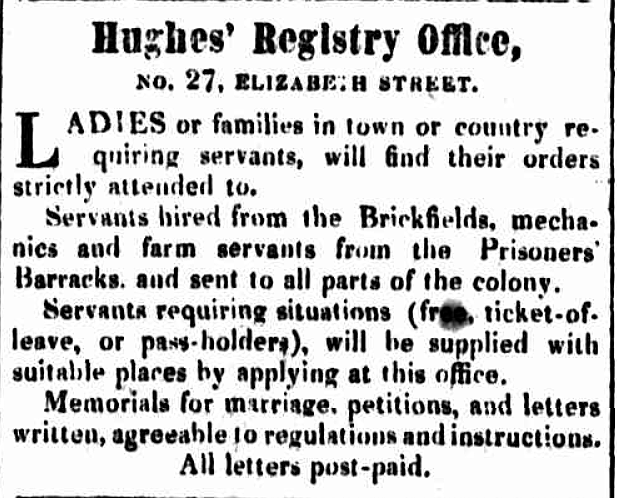

Under ‘Remarks’ on the conduct sheet are recorded Henry’s Convict Labour Contracts, giving the date of commencement, employer and place of employment. Not many of these contracts have survived, however, Henry’s final contract, with a J[oh]n Hughes, Elizabeth Street, has survived to be digitsed.25

It is likely this was the same Hughes who ran a Register Office at 27 Elizabeth Street. Ironically, Henry may have been hired to clerk for a company who found work placements for other pass holders!

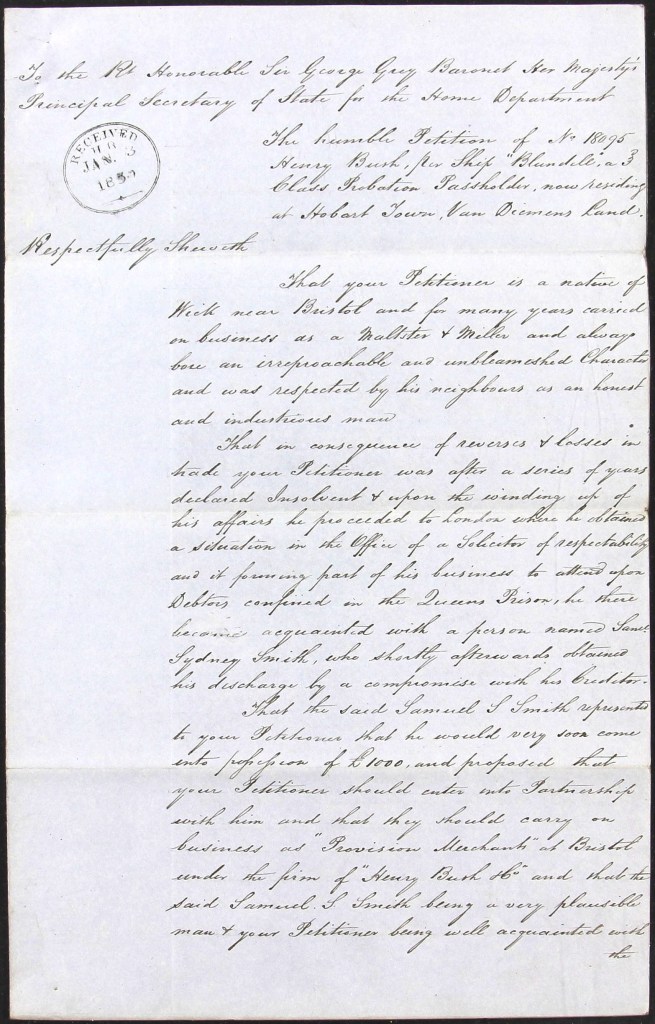

Although Henry was a ‘lifer’, with continued good behaviour, he could apply for a conditional pardon after ten to twelve years. This was not a Certificate of Freedom but would have allowed Henry to be free as long as he remained in the colony.26

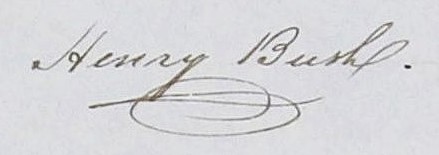

Henry applied to Sir George Grey, Secretary of State for the Home Department. The application, in Henry’s writing, is his account of the charges and trial. He presents himself as an honest man, duped by a swindler. Now fifty-two, after enduring “a great deal of mental, and bodily suffering”, he is ready “by honest industry…[to] gain a competence, to support his declining years.”27 The petition is signed with a flourish.

Henry’s petition was refused.

Henry must have been disappointed. Up to that point, he had been a model prisoner. Unfortunately, forgery was one of the highest classes of crimes. Prior to the option for transportation in 1837, forgers were hung. 28

Forced to accept his fate, for at least a few more years, Henry’s only respite from the Barracks was work – and that was a double-edged sword. Leaving the barracks increased prisoners’ exposure to ‘ordinary’ life, and Henry’s conduct sheet reflects this. For being “Drunk” in August 1849 he was “Reprim[ande]d”. Four months later, again for drunkenness, he received three months imprisonment and hard labour on Public Works (building roads, wharves or bridges). On 4 June 1850, for being “Out after hours” he received one month’s “imp[risonmen]t and hard lab[our]”. For his final offence, just a short time after returning to work, for being “Drunk and out after hours” in July 1850, he was given a fortnight in solitary confinement.

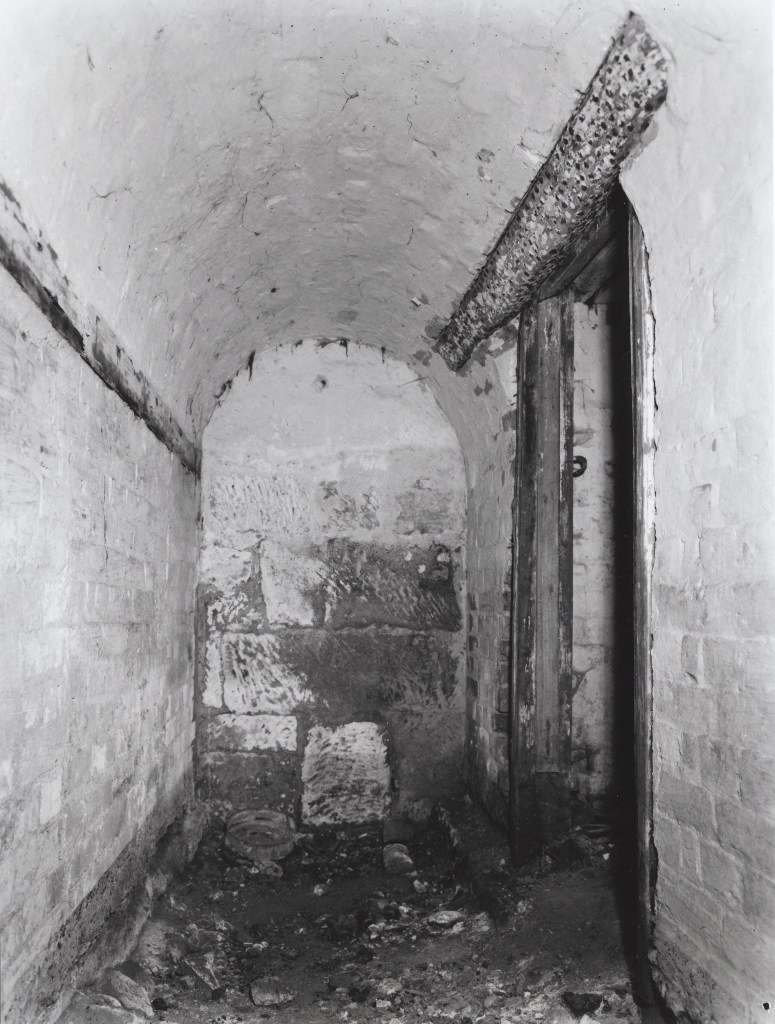

Hobart’s solitary cells were tiny and underground, with thick stone walls. They were cold year-round, but particularly bad during a Tasmanian winter. Prisoners endured a diet of bread and water.29

Henry’s convict record notes he “returned to service” on 3 August 1850. Perhaps during his time in solitary, Henry caught something or perhaps he was just worn out. On 26 August 1850, Henry was transferred from the Barracks to the Colonial Hospital.

The Colonial Hospital

Medical care for convicts in Hobart was provided in the Colonial Hospital in Liverpool Street. The building was two stories high and had four wards. It could accommodate 56 patients but at times took up to 70.30

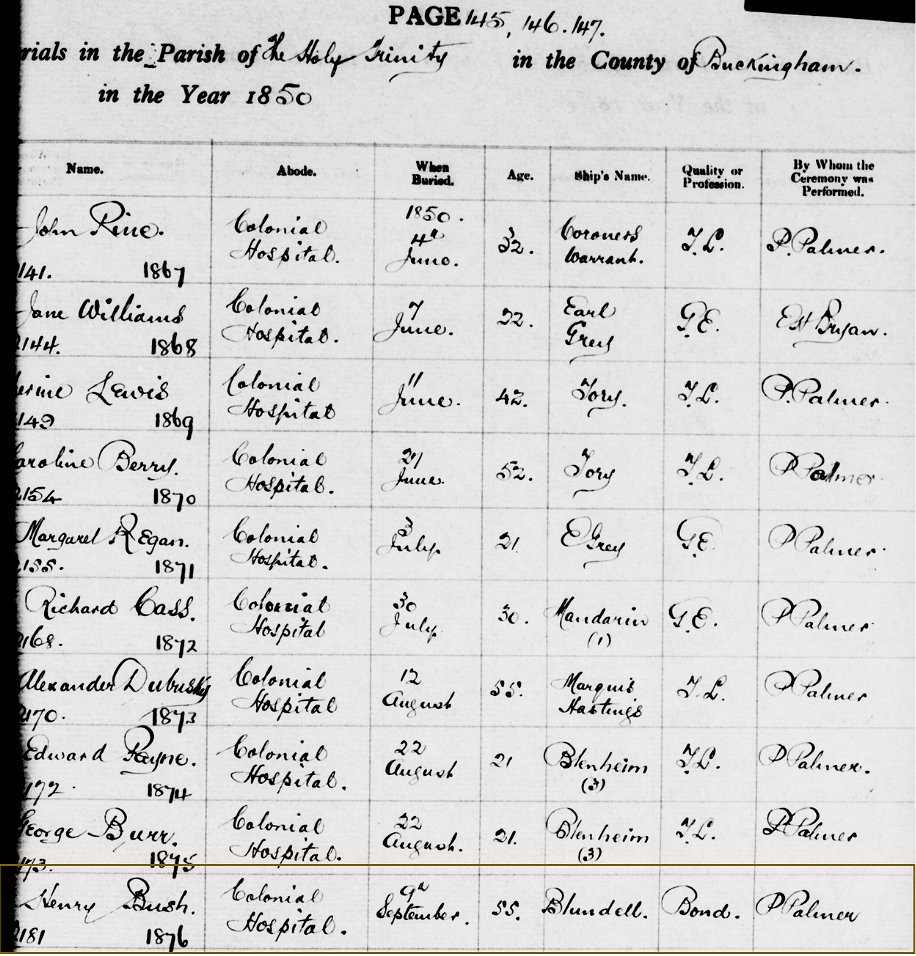

Henry died at the hospital aged fifty-three (recorded as fifty-five) on 6 September 1850. He was buried three days later at the Holy Trinity Prisoner’s Burial Ground in Campbell Street. Prisoners were generally afforded some measure of respect, given some form of service (provided by the Minster Philip Palmer), coffins and prepared graves.31

Today the burial ground lies underneath a primary school. A monument has been erected for the some 5000 free settlers and convicts who were buried there between 1831 and 1872.32

Over 69,000 male and female convicts arrived in Van Diemen’s Land between 1803 and 1853. At any one time, thousands were incarcerated or employed across the length and breadth of the colony. Inevitably, many died while still under sentence, my ancestor Henry Bush being one of them.33

Have you researched your own convict relative(s)? Perhaps you weren't aware of how many sources are available or where to look. I found this research satisfying and exciting all at the same time. My next step is to obtain Henry's death certificate to determine what he died from.

Sources:

- “Bristol, England, Church of England Burials, 1813-1994,” imaged at Ancestry, George Bush, 44Y, buried 11 Aug 1814, Abson, St James, Gloucestershire, England; Bristol Archives, Bristol, Bristol Church of England Parish Registers, Ref: P/Abs/R/4/A. Also, “Gloucestershire: To Maltsters”, Gloucester Journal, 11 Dec 1815, p.1; FindmyPast Newspapers. ↩︎

- “Married,” The Bristol Mercury and Daily Post, Western Countries and South Wales Advertiser, 3 May 1819, p.4; Newspapers.com. ↩︎

- “Bankrupts”, The Salisbury and Winchester Journal, 29 Mar 1819, p.4; Newspapers.com. Also, “Wick and Abson, in the county of Gloucester…”, The Bristol Mirror, 22 May 1819, p.2; Newspapers.com. ↩︎

- “NOTICE. All persons having any claim…”, Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal, 25 Mar 1826, p.2; Newspapers.com. ↩︎

- During the trial, Henry admitted he had not “slept there [Stout’s Hill] for many years.” See ‘Trial of SAMUEL SIDNEY SMITH’, Old Bailey Proceedings Online, 21 Aug 1843, Ref No. t18430821-2275. ↩︎

- “BUSH, Henry, of Wilsbridge near Bristol, farmer”, Perry’s Bankrupt Gazette, 12 Apr 1834, p.5; FindmyPast Newspapers. ↩︎

- “London, England, King’s Bench and Fleet Prison Discharge Books and Prisoner Lists, 1734-1862”, imaged at Ancestry, George Bush, Fleet Prison, discharged 14 Oct 1836. ↩︎

- “The Court for Relief of Insolvent Debtors”, Gloucestershire Chronicle, 24 Feb 1838, p.2; FindmyPast Newspapers. ↩︎

- “Insolvent Debtors Court”, Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, 22 Mar 1838, p.3; Newspapers.com. ↩︎

- “1841 England Census”, imaged at Ancestry, Gloucestershire, Bitton, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 14, Class HO107, Piece 361, Book 18, Folio 34, page 20 (stamped), Longwell Green, Hamlet of Oldland, line 5, household of Martha Bush 40y, Independent; National Archives of the UK (TNA), Public Record Office. Also, “1841 England Census”, imaged at Ancestry, Gloucestershire, St Marys Redcliff, population schedule, enumeration district (ED) 9, Class HO107, Piece 373, Book 4, Folio 35, page 20 (stamped), Redcliff Hill, line 2, Ann M Bush 10y, pupil; National Archives of the UK, Public Record Office. ↩︎

- Blake, Paul, “What is a debtors’ prison?” Who Do You Think You Are? (https://www.whodoyouthinkyouaremagazine.com/feature/the-fascinating-history-of-debtors-prisons : published 30 Nov 2023). ↩︎

- “CENTRAL CRIMINAL COURT, Monday, Aug. 28”, The Times (London), 29 Aug 1843, p.6-7; Newspapers.com. ↩︎

- “Police Intelligence”, Morning Post (London), 7 Jul 1843, p.7; Newspapers.com. Also, “CENTRAL CRIMINAL COURT – Aug 28.”, Shipping and Mercantile Gazette, 29 Aug 1843, p.4; FindmyPast Newspapers. Also, “CENTRAL CRIMINAL COURT, Monday, Aug 28.”, Evening Mail, 30 Aug 1843, p.3; FindmyPast Newspapers. Also, “CENTRAL CRIMINAL COURT, Monday, Aug.28, Forgery”, London Evening Standard, 29 Aug 1843, p.4; FindmyPast Newspapers. Also, “CENTRAL CRIMINAL COURT.-Monday, Extraordinary Case of Forgery”, Bristol Times and Mirror, 2 Sep 1843, p.1; FindmyPast Newspapers. ↩︎

- Willetts, Jen, “Convict Ship Blundell 1844,” Free Settler or Felon. ↩︎

- “To the Editor of the Review”, The Austral-Asiatic Review, Tasmanian and Australian Advertiser (Hobart Town, Tas.), 17 Aug 1844, p.6; Trove<http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article232482945>. Also, “UK, Royal Navy Medical Journals, 1817-1856”, imaged at Ancestry, Medical journal of the Blundell , convict ship, for 29 February to 1 August 1844 by Benjamin Bynoe; National Archives, Kew, Admiralty and predecessors: Office of the Director General of the Medical Department of the Navy and predecessors: Medical Journals, Ref: ADM 101/12/7. ↩︎

- Griffiths, Arthur, Memorials of Millbank and chapters in prison history (Chapman and Hall, 1884):316; Internet Archive. ↩︎

- Mortimer, Brenda, Dr., Norfolk Island: the ultra-penal colony, blogpost, (https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/explore-the-collection/the-collection-blog/from-our-volunteers/norfolk-island-the-ultra-penal-colony : published 13 Jun 2025); The National Archives. Also, Jauczius, Jenny, “Grim Punishment”, NorfolkIsland.net; first published in YourWorld, 5 (2), 2015. ↩︎

- “England & Wales, crime, prisons & punishment, 1770-1935”, imaged at FindmyPast (https://www.findmypast.co.uk/transcript?id=TNA%2FCCC%2F2C%2FHO18%2F00264672), Henry Bush, maltster and miller, petition for pardon; National Archives, Kew, Home Office: criminal petitions, part 2, Ref: HO 18/267. ↩︎

- “Exhibitions: Commissariat Store,” Norfolk Island Museum (http://norfolkislandmuseum.com.au/exhibitions/commissariat-store) ↩︎

- “Tasmania Convict Records 1800-1893”, imaged at FindmyPast, conduct record of Henry Bush, arrived per Blundell 6 Jul 1844; Tasmanian Archive & Heritage Office, Conduct Record CON33/1/78; Indent CON17/1/2 p36. ↩︎

- “Convict Indent”, imaged at Libraries Tasmania (https://libraries.tas.gov.au/Digital/CON17-1-2/CON17-1-2P40), Henry Bush; Indents of Male Convicts arriving from Norfolk Island 1844-1852, Ref CON17-1-2 images 40-41. Also, “England & Wales, crime, prisons & punishment, 1770-1935”, imaged at FindmyPast (https://www.findmypast.co.uk/transcript?id=TNA%2FCCC%2F2C%2FHO18%2F00264672), Henry Bush, maltster and miller, petition for pardon; National Archives, Kew, Home Office: criminal petitions, part 2, Ref: HO 18/267. ↩︎

- Gibbs, M., Tuffin, R. “Carceral Time at Port Arthur and the Tasman Peninsula: An Archaeological View of the Mechanisms of Convict Time Management in a Nineteenth Century Penal Landscape”, Int Jnl Historical Archaeology (2024) 28, 856–881 (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-024-00734-w). ↩︎

- “Conduct Record”, imaged at Libraries Tasmania (https://libraries.tas.gov.au/Digital/CON33-1-78/CON33-1-78p34), Henry Bush, Blundell; Conduct Registers of Male Convicts arriving in the Period of the Probation System, Ref: CON33-1-78, image 34. ↩︎

- Oxley, Deborah, “VDL Convict Labour Contracts 1848-1857”, Digital Panopticon (https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/VDL_Convict_Labour_Contracts_1848-1857 : last updated 2020). ↩︎

- “Employment Record”, imaged at Libraries Tasmania (https://libraries.tas.gov.au/Digital/CON30-1-1P456), entry for Henry Bush, 19 Jul 1850, employer John Hughes, Elizabeth St; Registers of the Employment of Probation Passholders (1848-1857), Ref: CON30/1/1 p255. ↩︎

- “How were convicts rewarded for good behaviour?” Museums of History NSW (https://mhnsw.au/learning/rewards-freedom) ↩︎

- “UK, Criminal Records, 1780-1871”, imaged at Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com.au/search/collections/61805/records/441732?) petition of Henry Bush of Wick, charge of forgery, sentenced to transportation; National Archives, Kew, Home Office: Criminal Petitions: Series II, Ref HO 18/267. ↩︎

- “Forgery Act 1830”, Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forgery_Act_1830 : last updated 20 Aug 2025). ↩︎

- Brown, M., Sussex, L., Outrageous Fortunes (Black Incl, 2025); Google Books. ↩︎

- “Colonial Hospital”, Find & Connect (https://www.findandconnect.gov.au/entity/colonial-hospital/). ↩︎

- Tuffin, R., “The Post Mortem Treatment of Convicts in Van Diemen’s Land, 1814-

1874″, Journal of Australian Colonial History, (2007), 9, 99-126; ResearchGate. ↩︎ - “Trinity Burial Ground & Prisoners Burial Ground”, Monument Australia (https://www.monumentaustralia.org/themes/landscape/settlement/display/104471-trinity-burial-ground-and-prisoners-burial-ground). ↩︎

- Tuffin, R., “The Post Mortem Treatment of Convicts in Van Diemen’s Land, 1814-

1874″, Journal of Australian Colonial History, (2007), 9, 99-126; ResearchGate. ↩︎

Subscription databases: Ancestry, FindmyPast, Newsapapers.com

Non-subscription databases: FamilySearch, Findagrave, Trove

Leave a comment